Land of Pura Vida

As I was saying in my last post, I love Costa Rica — which I wrote before even landing when I looked out of the window of our plane and decided I could comfortably judge this book by its cover. And Costa Rica’s cover is really green and lush and full of life. Within the first couple days I might have used the word “lush” about a hundred times or so as we went from place to place and saw mossy trees sparkling with water droplets and mini waterfalls oozing out of rocks along the roads, just commonplace features of your surroundings here that would probably be considered “must-visit” sights back home if you could somehow cut and paste them into central Texas.

Costa Rica’s signature phrase comes to mind: pura vida. It literally means “pure life” but is apparently used constantly as a kind of slogan for being laid back, alive, and just grateful to be around. Maybe I’m off on that one, but I hope to unpack it more throughout the trip. For now I’ll just take it literally, for pure life was all around me.

One of the first moments that brought that feeling to life came on our very first morning at our jungle bungalow. It was a basic A-frame house covered in windows embedded in a jungle property that felt a tad sketch getting to as there wasn’t really an entrance from the road or anything — just a metal sliding gate that was held together with a bike lock — but the property was pure magic and had its own private trail leading to a stream with light rapids in some parts and then a perfect swimming hole in another part with little offshoots pretty much designed by nature for boogie boarding.

So we hopped in and frolicked and boogie boarded and basked in the joy of the jungle beauty all around us — blue butterflies swooping down towards us, toucans croaking from somewhere in the trees, a constant chorus of insects, and I even saw a green basilisk, which is a lizard with a pointy crown on its head and a fascinating ability to run across water, earning it the nickname the Jesus Christ Lizard. Jesus, what a cool creature.

It’s moments like these that you just want to bottle up and save forever.

And we were just getting started.

Life All Around Us

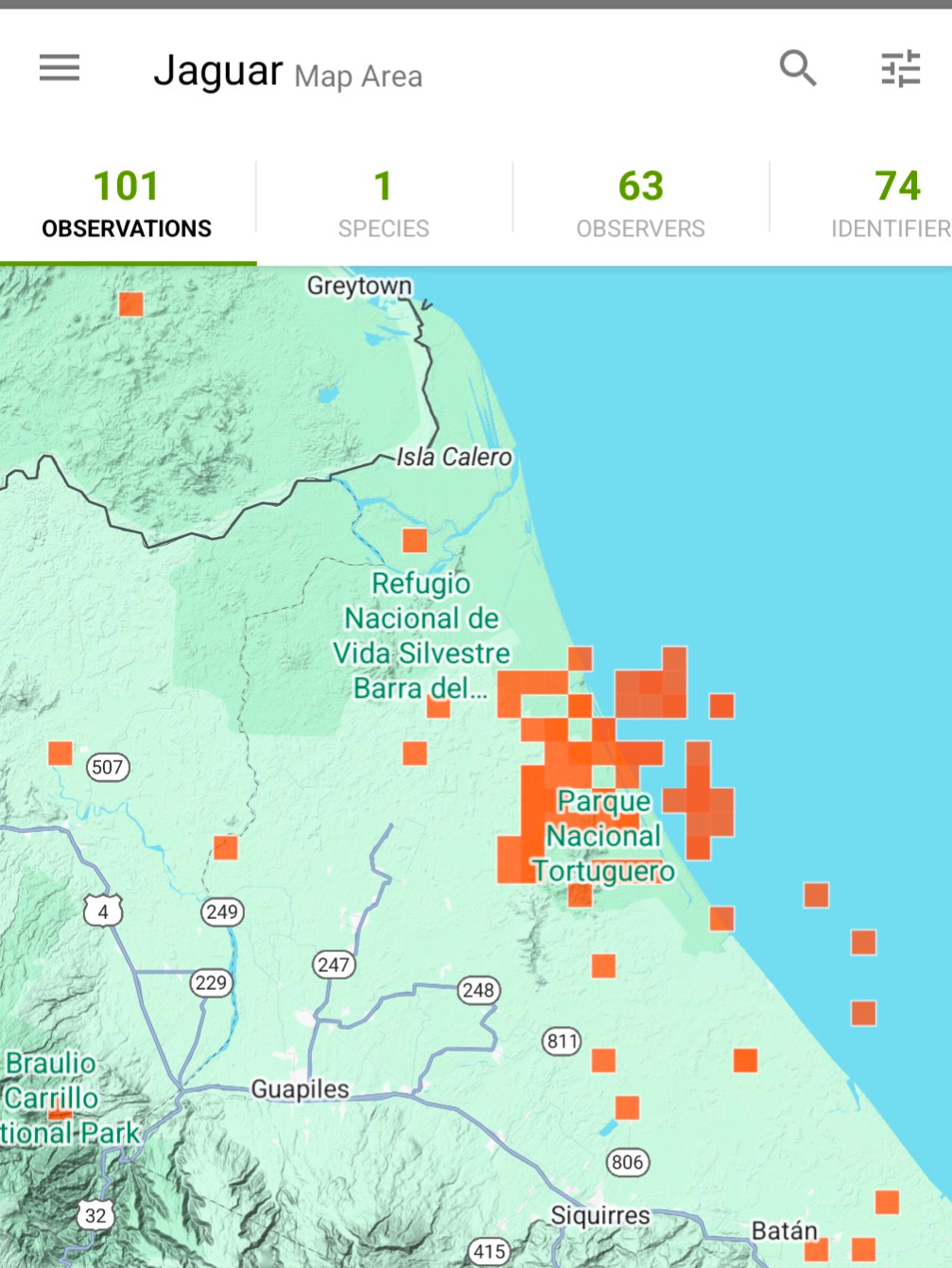

The Airbnb was only a pit stop on our way to Pavona where we would take a boat the next day to Tortuguero National Park, a car-free area around 100 square miles renowned for its turtle nesting season which happened to overlap with our trip. While we had already been in the jungle, stepping onto a boat that would take us an hour away from any roads felt like stepping into the true wilderness. Some say Tortuguero is Costa Rica’s own “mini Amazon” with its rivers and canals slithering through tropical jungles teeming with all kinds of creatures. Besides sea turtles, it’s particularly known for its jaguar population, although they are rarely spotted. But they’re out there. And that just made me giddy to think about. One guide I talked to who grew up in the area and spends pretty much every day in the rainforest said he’s seen them about a dozen times in his entire life.

To get a grasp on what else is out there, I leaned on the iNaturalist app quite a bit. You can search for any species, genus, family, etc. for any given area and see observations that people have submitted, which are then vetted by expert community members who validate them as “research grade” sightings funneled into a database for scientists to do their fancy studies and such. When you sort them by most frequently observed you can get a pretty quick idea of some species you might encounter. I did this for each of the areas where we’ll be staying across some of the main groups, like snakes, lizards, frogs, birds, and mammals. Here’s what we were in for in Tortuguero:

Of course, animals generally don’t like being seen by scary humans so we would only see a handful of these, but again, they’re out there. And knowing that this was the closest I had ever come to wild eyelash vipers and strawberry poison dart frogs already had me stoked.

Merlin Bird ID app by Cornell Lab of Ornithology has been another amazing tool specifically for learning about birds around us. You can hit a button to start recording and it matches bird sounds around you with thousands of bird sounds in its database. I just left it on throughout the day to discover birds like great green macaws, toucans, hummingbirds, Montezuma oropendolas, and others were right by us, and then we’d pull out the binoculars and start searching.

One neat thing about Costa Rica is that the whole tourism industry is basically centered around their biodiversity, possibly more so than any other country on Earth. Its vibe is basically like if Rainforest Cafe was a country.

It wasn’t always like this though. In fact it used to have one of the worst deforestation rates in the world, but by 1980s they took aggressive measures to reverse this by establishing national parks and protected areas (over a fourth of the entire country’s land), creating biological corridors to connect fragmented ecosystems, and investing heavily in environmental incentives to pay landowners to conserve or reforest their land, in part funded through a gasoline tax. Beyond this, they leaned into branding as an “eco-paradise” to attract nature nuts like me, along with certification systems to rank hotels and businesses on sustainability.

You see the impacts of this everywhere. On the plane I saw at least a couple people with guidebooks for birds and other animals, and I was of course among them with my book on Reptiles of Costa Rica. Walking around our hotel of Tortuguero, it was common to see people walking off the paths to poke around a tree or bush for some lizard or other creature they spotted, or pointing their eyes up towards the trees where a macaw or toucan had landed. Usually I feel like a total weirdo walking around a hotel property at night with a flashlight looking for snakes, but here there’s nothing weird about it as lots of tourists are eager to see the nocturnal animals and roam around even in the darkness. Many hotels offer guided “night walks” specifically for this purpose.

Another example was when we were driving towards La Fortuna after Tortuguero and saw a line of five cars and a small bus pulled over with a dozen people or so pointing up at something in a tree. Of course, we pulled over to see what the fuss was about and someone told us there was a “perezoso,” one of Costa Rica’s most beloved animals: the sloth. I frantically got everyone out of the car and ran over when it hit me that there really wasn’t a rush. This was a sloth after all and it wasn’t going anywhere, too quickly at least. And what a cool creature it was.

But the highlight so far was something I wasn’t really expecting.

Life Against All Odds

I’ll be honest -- as much as I’m into my biodiversity and especially reptiles and amphibians, I figured most people were probably exaggerating a bit when they’d describe seeing the sea turtles do their nesting as a “moving” experience.

Well, I was way wrong about that. To be fair, I’m rather easily moved, but still, I was caught off guard when we saw it for ourselves our first night at Tortuguero. It was around 10pm on a beach just minutes away from our lodge under a moonless sky that was just glimmering with stars, and we huddled in groups of eight people per guide as required by law, all in dark clothes, no lights, no cameras or phones aside from a red flashlight the guides used. And for the first 30 minutes or so we just waited.

“She’s almost ready” the guide kept telling us. The humidity was absolutely sweltering and we were all pretty uncomfortable, but apparently just 50 feet or so away from us was a green sea turtle digging in the sand, getting ready to lay her eggs, and that’s what we had all paid to see. The turtles are what make Tortuguero such a special place after all as one of the biggest turtle nesting sights on earth and the largest in the Western Hemisphere. Between the months of July and October tens of thousands of turtles swim across thousands of miles to this 22-mile stretch of land where the sand and climate are just right for incubating millions of little turtle eggs. Our guide said around 1000 mother turtles will lay their eggs within that stretch of land on some nights.

We would see just one of them.

I think most of us have heard about the poor baby turtles that rarely end up surviving past their first few minutes of life — gobbled up by birds, crabs, ants, and other predators just waiting for the buffet to hatch — but the numbers were even more staggering than I’d realized.

“One in a thousand will survive” the guide told us. And each mother turtle may lay 100-150 eggs up to five or six times throughout the season, which — if my math is right — means a mother turtle will be lucky to have even one of her hundreds of babies survive each year.

The odds of reaching adulthood are even lower, with some estimates showing that 1 in 10,000 will live that long.

At one point the guide pointed his light to the shore where he spotted another turtle swimming back into the ocean. He explained that she had picked a spot where the beach was too steep to get out — as a small cliff of sand stood in her way. But he said she’d be back later to try again.

We finally lined up to have a turn observing the mamma turtle lay her eggs. We would each have 3 or 4 turns, and each would be less than a minute long. And wow, I’m not sure how large I thought sea turtles were, but it was so much larger than I expected, about 4 or 5 feet long and 3 feet wide. The guide pulled up one of her back flaps (or feet?) to give a view of where dozens of ping-pong ball-sized eggs were piled in a large hole in the sand. Every 10 seconds or so another one or two more would drop.

She was in a complete trance state the guide told us, which is fascinating to think about, just the fact that nature spawns beings such as this one that essentially follow a script provided by nature herself to spawn more beings. And eventually those beings hatch and run towards the water without any clue of the reason or what the hell this place even is.

Just run little guys, run. That’s what nature is telling you to do.

Once the eggs are all laid, the mamma turtle spends the next hour or so covering it up and just as much time camouflaging the area to keep it inconspicuous and safe from predators. I thought about the barn swallows we have back home where we’ve seen a mamma bird over the last few months first build the nest, then lay on her eggs, feed the chicks, and eventually move on once they fly out of that nest a few weeks later. And for an even greater contrast there are humans, which are probably the most extreme example in the animal kingdom, keeping our babies in our “nest” until the age of 18, give or take.

But once that mamma turtle walks back to the ocean, that’s the last interaction she will ever have with her babies.

Maybe that’s what made it feel so moving — just all that goes into bringing life into the world, all those miles travelled and all that time and effort crammed into this short window of time on this short stretch of land that I got to witness under a glimmering sky in the cosmos, all for just one little turtle to hopefully make it.

Or maybe I’m just an easily-moved ape spawned from a single sperm and egg that were paired together against staggering odds back in the day and eventually found its way to a place like this.

Maybe it’s that.

Anyways, I had a bunch more to share, but in the spirit of pura vida, let’s get back to living and save the rest for another one as I keep peeling back what this whole pura vida thing is all about.

With love from Planet Earth,

Doug