Lots of Snakes and Words in La Fortuna

Last night I did something the average human would probably consider a terrible way of spending an evening. It involved rubber boots, flashlights, snake hooks, and a good four hours of hiking through ranch land mixed with rainforest and rural gravel roads on a muggy July night in Costa Rica surrounded by bugs, spiders, and snakes.

I even paid money to do it. And it’s easily the highlight of our trip to Costa Rica so far.

This was a tour that’s been in the works for at least a year and one of the reasons I’ve wanted to visit Costa Rica in the first place. By “in the works” I mean I reached out to a company who offers “herping” tours in the area to find reptiles and amphibians. My dream is still do one of their lengthier expeditions like the 15-day “Viper Herping Tour” across different regions to try maximize the probability of finding “21 of the 23 vipers and coral snakes” of Costa Rica, but that wouldn’t overlap too well with a family trip so I opted for a night walk instead.

Unlike other nature tours we’ve done throughout the trip (like the sea turtle nesting and jungle night walk), the guides for this one were actual biologists and herpetologists. Victor was the main guide, a tropical biologist who studies snake venom and says he has found more than 18,000 snakes in his life, starting at the age of 3 when he’d go out with his father who has been a biologist for over 40 years now.

Victor says his dad (also named ‘Victor’) knows pretty much everything about every animal out there and he’ll often call him up while on a walk to help identify some random bug, spider, frog, or anything else he’s not sure about. Lucky for me, he also tagged along for the walk to help find some our target species. For me that was the eyelash viper, fer-de-lance, and pretty much any other snake. But especially those.

We drove our 4x4s down a windy road not too far from La Fortuna and pulled up to a barbed wire fence hiding behind an overgrown path on the edge of some farmland dotted with huge trees, logs, and cow pies. I didn’t see any cows though. They throw the farmer $15 to get access, and in return he leaves the snakes alone instead of killing them and lets the Victors roam the property. Win-win-win for the farmer, biologists, and snakes. And me of course.

The Most Feared Snake in Costa Rica

Already within five minutes of arriving, Victor Sr. yelled that he’d found something.

It was a Terciopelo — also known as the fer-de-lance. This one was a juvenile crawling at the base of a tree just outside the fence, perhaps two feet or so in length with a skin pattern that would easily blend in with dead leaves. Some get up to 8 feet in length. When I had asked our turtle nesting guide a few days back what animal he feared the most he said it was this one.

Victor agreed. He said he personally knows at least three people who took a bite, and each of them happened when stepping over a log, their favorite place to hang out and ambush prey. A bite will often send you to the hospital for weeks. Around 650 occur each year in Costa Rica, and it’s usually farmers. Less than 1% are fatal, but it’s still a terrible bite to take.

Just look at that head. They just look like they mean business.

For Victor, the Fer-de-lance is one of the more commonplace snakes to find and less interesting than some others since there isn’t much variation in how they look.

Eyelash vipers on the other hand — while also pretty common — have all kinds of variations in skin color, patterns, and even eye color, which make them one of Victor’s favorite snakes to find despite how common they are. Most of them are a greenish-grayish color with shaded blotches, but Victor said he finds the iconic bright yellow variation, aka the “golden eyelash viper” about every 3 out of 10 walks he does. About 30 minutes to the south of us he said there’s an entire isolated population that doesn’t have any pattern at all. The most unique he’s ever found was completely black with gold-colored eyes.

We wouldn’t find one that rare, but turned out our luck was pretty good.

Our First Eyelash

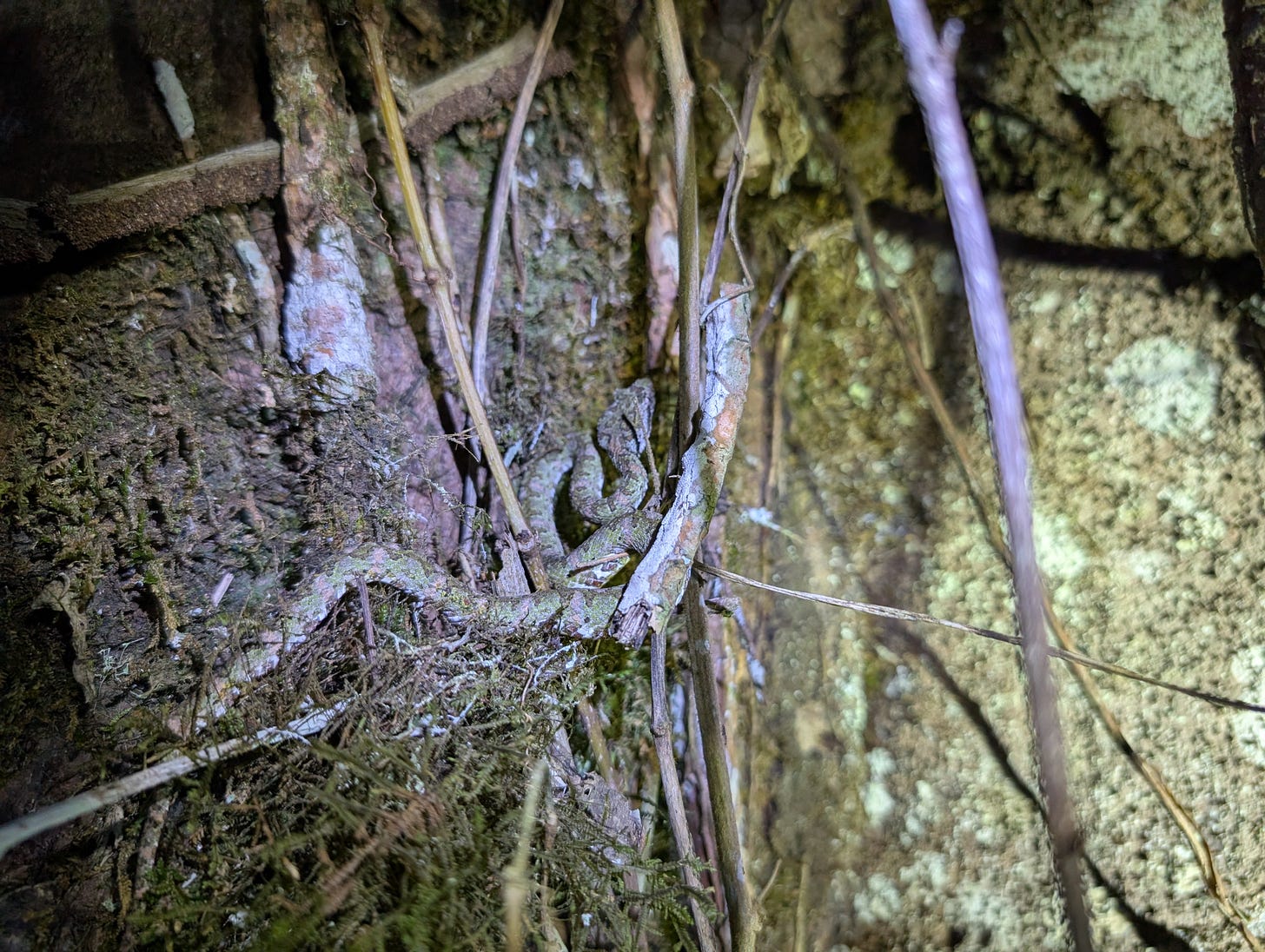

About 20 minutes after the fer-de-lance Victor Sr. yelled back again that he’d found another snake. His flashlight was pointed about 8 feet up the trunk of a tree covered in mosses, lichens, and winding vines where an eyelash viper perched in a bark’s crevices and blended in perfectly. About two feet long, it was mostly green but also had some pinkish blotches, which Victor described as a “Christmas morph.”

What a stunning creature.

It only took another 10 minutes until we found our next eyelash. Again, it was Victor Sr. This time he didn’t point out where it was but just said to come closer and look around. A good 15 feet up the trunk of a towering tree wrapped in plants and vines growing out of it, there it was. In fact, you really couldn’t miss this one. Cuz we had found the golden eyelash viper, and boy does that yellow pop.

What an incredible freak of nature:

Even if we found nothing else the rest of the walk, I’d go home feeling incredibly happy.

And yet, we kept finding stuff.

We found a coffee snake, which are one of the more common nonvenomous snakes in the area, a tiny guy at the base of a tree that I actually spotted (pretty sure it was the only snake I found on my own of the night).

We found a ringed snail sucker (Sibon annulatus) which was another snake I’d hoped we’d find. These guys slurp up snails by hooking them with their teeth and slowly walking their upper and lower jaws over the body bit by bit until the soft part is pulled from the shell. Super cool snake.

The helmeted iguana was another cool one. It’s the only basilisk that can’t run on water, and I think they’re the coolest looking ones too, like mini-dinosaurs.

And we found a bunch of frogs, including the South American Bullfrog (Leptodactylus pentadactylus) that can get to be the size of a football, although the one we saw was quite a bit smaller. There was also a rain frog, glass frog, red-eyed tree frogs, and some others — I don’t know my frogs as well as snakes though.

Also lots of neat insects, spiders, and millipedes, including a “wandering spider” which has a neurotoxic venom that Victor says can send you to the hospital.

I don’t recall the name of all of these, but here are a few:

Annnd even another eyelash viper ... but it still wouldn’t be our last.

Lifey Chats and Big Picture Stuff

We eventually worked up an appetite and drove to Victor’s home town of El Castillo about 20 minutes away to stop by a soda (i.e. traditional Costa Rica restaurant) for some food before heading to our last spot. It was around 10pm and the soda was usually closed at this hour, but they often stay open late for Victor and his guests and seemed to run a pretty casual operation.

The conversations were at least as interesting as the snakes we found, and even that alone would have made the night worth it.

Victor told me about what it’s like trying to get by as a biologist, saying he actually earns more with his tours than his academic work. Patching together different income streams seems common in the field, unless you find some breakthrough or practical application, like a new venom treatment or snake repellent for the market. One of his colleagues is even a full-time programmer at AT&T and just does his snake stuff on the side.

Meanwhile AI is starting to gobble up the programming jobs, so who knows how long that will be safe.

“The biggest lie anyone ever told was that you are secure.” Victor said about this. After all, species are adapted to environments, and if the environment changes or another species takes your place, you either adapt or die. It’s the classic “Survival of the fittest” and natural selection all the way down.

The Victors also used to have a zoo of their own with more than 400 animals, including lots of snakes and other animals that were rescued from authorities who had confiscated them. But after the pandemic they had to shut down and were never able to get the permits to start it back up again. Victor said it was a really hard time for them, as lots of other things seemed to compound at the time and life took a turn.

It seemed like a sore topic and a bit of a vibe shift bringing it up. But we talked about a bunch of other stuff too.

Like new species discoveries and how there’s so much more to be found in the insect world than vertebrates like snakes, largely due to their rapid lifecycle that allows for genetic mutations to spread through populations faster than animals like snakes that live much longer. Each short generation is another roll of the dice genetically speaking, which means more chances to change and ultimately a greater variety of species. Just look at the animal kingdom: insects account for at least 75% percent of all of the 1.5 million animal species, and some estimates say there are more than 10 million yet to be discovered.

What a fascinating and mostly-undiscovered world it is out there, always changing, adapting, evolving.

Final Stroll (we’re almost there, I promise)

By now it was getting late and they still wanted to try one more spot, and I was down to go for as long as they were. For this one we drove up a bumpy, narrow mountainside road and then walked back down it to scan trees on both sides for snakes. Our snake count for the night was already at 6, including that golden eyelash that they usually don’t see, which felt pretty good already. Could we squeeze in another one or two?

As it turned out, we could. Victor and I were scanning the thick brush of trees on the right side of the road for a few minutes, when Victor Sr. caught up with us and suggested we look at the left side instead — even though the vegetation was quite a bit less dense.

Within no more than 30 seconds, we saw our second golden eyelash viper shining from a tree branch. This time it was even closer to us.

“The old man knows!” Victor laughed.

Our final snake turned out to be the same as the first, yet another of the “commonplace” fer-de-lances, except this one was in an extremely uncommon place: high up in the branches of a tree. Victor Sr. said he had only seen this species in a tree just three times in his entire 40+ year career as a biologist.

I get why these guys still get excited searching for snakes each night, even after 18,000+ finds. You just never know what you’ll see.

And what a fascinating way to make a living. Most humans — and all species for that matter — do the things they do merely as a means of survival and don’t necessarily enjoy it all that much. But Victor says he loves his work as a guide, and in some ways he also believes it may have even more impact than his formal biology work, as it spreads knowledge and care for the living world.

A small dent, perhaps — but lots of small dents can add up to something pretty incredible. Just look at those million-plus insect species.

Anyways that was a lot of words to say: I saw a bunch of snakes and it was awesome.

Tomorrow we head to Monteverde, where I hope to spot a snake that thrives more in that region: the side-striped palm pit viper. Let’s see how my odds play out.

From Planet Earth,

Doug