The Grossest Animal

One thing I’ve learned throughout my vast explorations of this planet is that people really don’t like animals living on them. Other animals probably don’t like it either, and I doubt dogs enjoy having fleas — but only a human will experience a visceral sense of disgust and lose their shit over just the thought, which makes us a pretty unique species.

And yet if you zoomed in on your face, you’ll find little critters like face mites and eyelash mites who have made themselves at home as permanent residents, while dozens more may visit us during our lifetime. Chances are you have hundreds or even thousands of their tiny faces burrowed in your face right now. Pretty neat huh.

If you have young children, there’s one in particular you’re likely to have in your household at one point or another. Some 6-12 million young children in the U.S. alone end up encountering it each year, more than there are kids with peanut allergies. Their scientific name is Pediculus humanus capitis — which, if I were representing this species, I’d probably stick with, since their common name has one of the worst reputations in the animal kingdom: head lice!

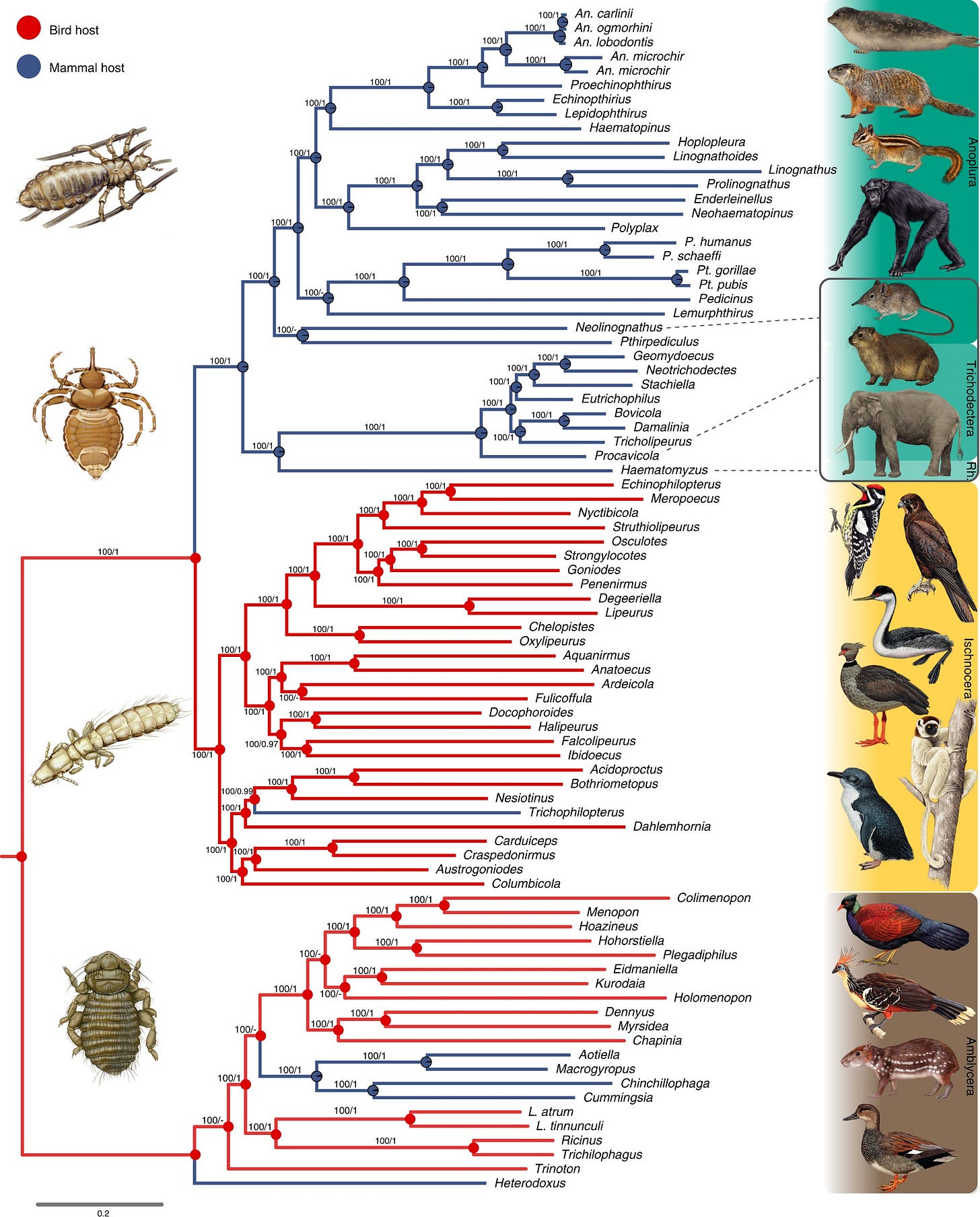

Even the word itself is jarring to hear, although the singular term “louse” sounds a little better to me for some resson. But really what’s in a name anyways? Would a louse by any other name be just as gross? Yeah, probably. But we’ll give them a fair shot, and from here on out I’m calling them capitis, at least for the head lice variety. There happen to be almost 5,000 other kinds of lice too, all part of the Phthiraptera order of animals which includes both chewing and sucking varieties. We’ll call those rapteras for now, just cuz it’s catchier than Phthirapteras.

Also I don’t really want to keep writing the word lice. Gross. (that’s the last one I promise). So capitis and rapteras it is.

My whole family had them just last week. Publishing such a thing is a great way to make everyone you meet run away, and borderline taboo, but luckily I’m an introvert. And for whatever reason I like to overshare things while hiding behind a monkey avatar.

Also, animals fascinate me. Really all of them. And the idea of a species that can only survive on a habitat known as Homo Sapiens — also an animal — is pretty interesting. And here it was, right on my head. I didn’t even need to go outside like I did for viper hunting and birdwatching in Costa Rica. How wonderful. So I guess let’s go capitis watching.

Why we’re wimps

To be fair to us sensitive weirdos of the animal kingdom, we’re not just the animal’s habitat, but also their food considering our blood is their only food source. And most animals don’t like being eaten by other animals.

But there’s a disgust that’s so visceral that anyone with capitis might even be embarrassed or ashamed to admit it to anyone. If your kids get them, you dread the chain of texts you need to send out to other parents of kids they’ve been around, like someone notifying recent intimate partners they have an STD (I’m sure it’s the exact same thing but fortunately I’m only guessing). If you mention it at a dinner party, faces will shriek and shrivel.

Some theorize this feeling of disgust towards capitis and other bugs has been with us for thousands of years as a mechanism that evolved to protect us from dangerous plagues and such. In its extreme form, you get a phobia towards bugs called entomophobia that stems from that same origin, causing not just disgust but a primal fear in millions of people. Many feel it just from seeing an image of bugs. And for some unlucky folks, there’s even a related phobia called trypophobia that can trigger panic and nausea by the mere sight of clusters of holes resembling parasite nests or diseased skin. Something as innocuous as honeycombs or bubblewrap can suddenly become a subtle danger cue at a primal level.

How interesting.

As a fellow weird animal, I’m also pretty disgusted by capitis. But let’s see if we can let fascination override ick and put on our curiosity hats (hoping they don’t have capitis in them). In the animal kingdom we’re all pretty much doing the same things to survive anyways — which basically boils down to eating, pooping, finding shelter, and making babies. And who knows, maybe you are to the Earth what a capitis is to you.

Aw, you and capitis have the same hobbies. How cute.

Capitis, and their habitat

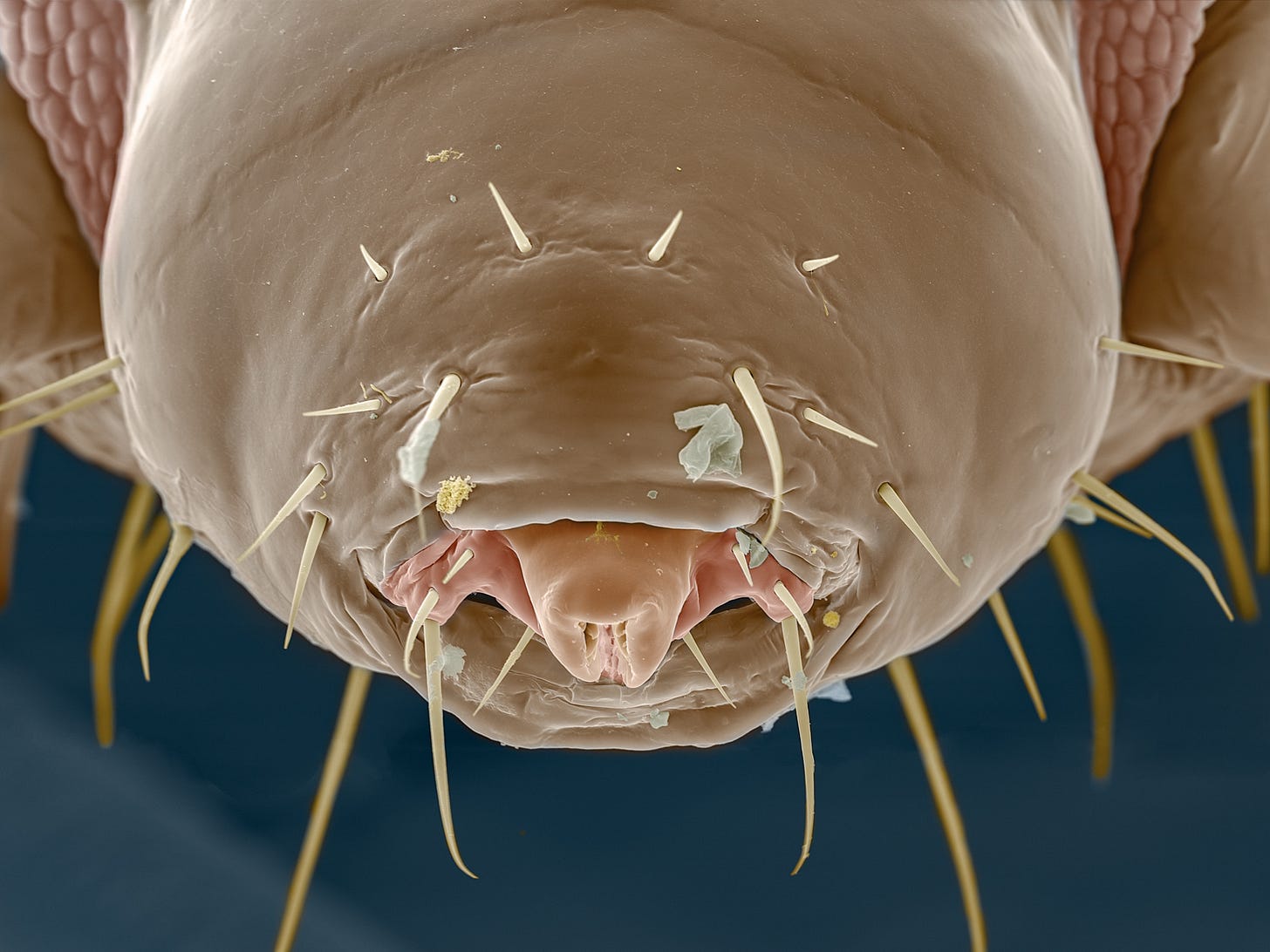

Unlike humans, capitis can’t really walk all that well, or jump or fly like other insects can. But they do have some unique body parts to get where they need (and here’s where it gets gnarly). Let’s zoom in on the main ones:

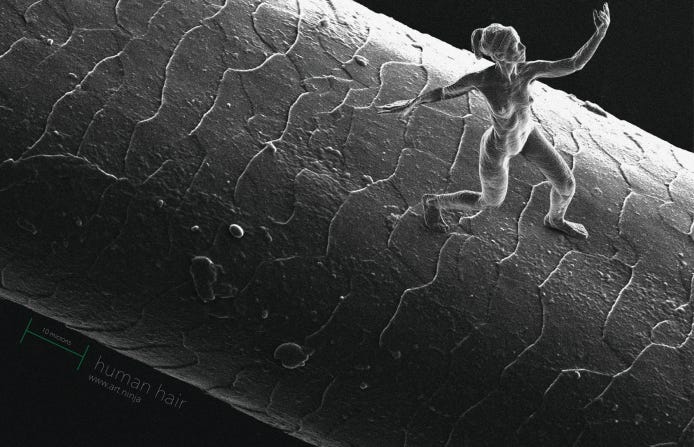

Specialized Latching Claws: They shimmy down your hair strands using hook-like claws that can grip each strand like a wrench on a bolt.

Scalp Anchor: Once they reach the skin they unfold their hidden mouthparts and anchor onto your scalp with tiny hook-teeth that grip the skin like Velcro.

The Blood Tap: Saw-like stylets slice into the skin and form a feeding tube that pumps saliva so your blood flows easier, then suck the blood out to eat drink and be merry.

They cannot survive for more than 48 hours anywhere that’s not a human head, so everything about them and their life cycle is adapted to staying put on this cranial island. That means they mate, lay eggs, and grow up all in the jungle of someone’s hair as a mostly self-contained ecosystem, except for those brave explorers who venture off to other heads or get stranded on pillows and hair brushes. A single head can host several hundred capitis in severe cases, but populations are usually much smaller and in most cases don’t even surpass 10.

Humans have it quite a bit easier, being adapted to pretty much every environment on Earth with an appetite for all kinds of things as we gorge on pigs, cows, chickens, or all three ground up and stuffed into a tube we call hot dogs. But capitis just drink our blood and leave it at that. How clean and sterile of them, almost like a hospital operation. I honestly didn’t even notice them on my head, and their famous itchiness isn’t as universal as most think and often only starts after a few weeks — although maybe that’s more horrifying. They could be on you, right now. And you might not even notice.

Their bodies have a translucent quality, so I was able to get a glimpse of this one’s last meal through my son’s little National Geographic microscope. Pretty wild seeing a blob of your own blood in its belly.

With such a basic diet, their poop looks like miniscule flecks and will never stink up a room like some species can. In fact you will never smell a capitis, but they will certainly smell you with their microscopic sensory organs on antennae that detect odors. Meanwhile they breathe through tiny holes along their sides that connect directly to internal air tubes. There’s no mucous production like humans have, and you will never hear a capitis hack out a loogey.

To mate, males wander around until they find a female to hook up with, literally clinging to her with tiny abdominal hooks and alternating between drinking blood and sleeping around to do their part in growing the population. Not too different from our own rituals, although human mating is apparently so disgusting that it’s best kept behind closed doors.

Eggs (or nits, as they’re often called) are then laid within 24 hours, just one or two per hair shaft at a time, and each is covered in a substance that basically cements it to the hair. Scrub your hair with shampoo all you want, but they’re not going anywhere and you’ll need a specialized comb and a chemical concoction to exterminate them. Heat from blow dryers can help too. She’ll keep producing 6-10 eggs every day for weeks, and they hatch after another week or so. It’s quite a bit cleaner than the messy process of mammal birth that humans will even describe as “beautiful” with a straight face (cuz bringing new life into the world is pretty rad like that).

Here’s how one of the eggs from our heads looked. Nothing like becoming an involuntary nursery.

Here’s how they look under a more powerful microscope:

After roughly another week and a few molts, they become full-grown adults about the size of a sesame seed.

Just days later they die at the ripe old age of ~30 days. They leave behind the surviving population who quietly perpetuate the cycle, and for the most part your “habitat” as a human looks the same as before, aside from small marks they can leave on the scalp. If they treated our heads like we treat our habitat you’d probably have whole patches of hair missing, overheated blood, and tiny smokestacks puffing smog at everyone.

Animals all the way down

Some people reading this might be throwing up in their mouths right now (a thought that gives me a visceral sense of disgust). Sorry for that.

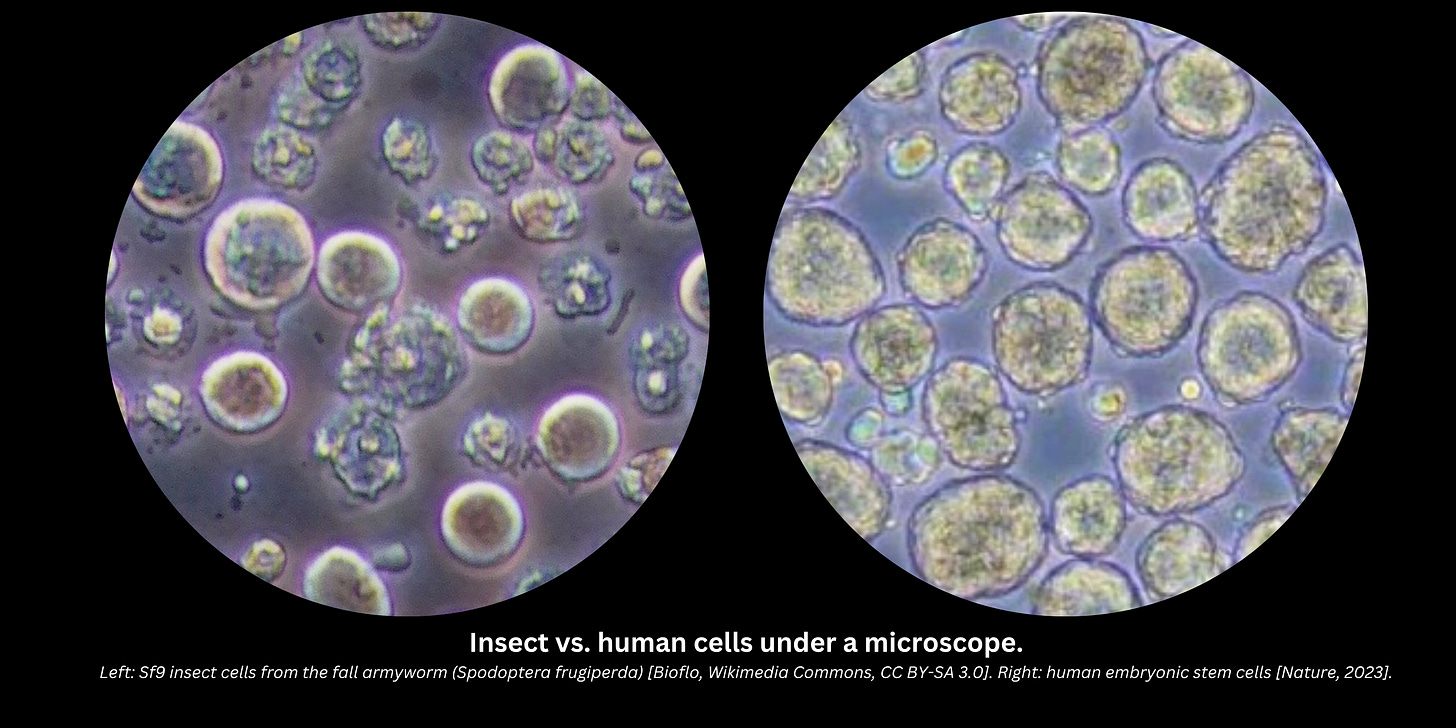

Maybe an even closer look will help. Zoom in far enough and you and capitis start to look almost the same — built from the same cellular machinery like membranes and nuclei and mitochondria running the factory of life itself. How interesting is it that we’re all mostly just different arrangements of the same tiny life bubbles.

It could be worse too. Each of the planet’s raptera species is specialized to live on a specific bird or mammal (reptiles, amphibians, and fish are somehow spared), and some birds can host dozens of species at once. There’s one kind that spends its whole life inside the pouch of pelicans (Piagetiella peralis), which must really suck. Another kind sucks the blood of pigs and can cause anemia and transmit swine pox to them (Haematopinus suis). Yet another (Bovicola bovis) lives on cows and causes “cattle pediculosis,” which comes with weight loss, lower milk production, and so much itchiness they often damage their hides from all the scratching.

But for the most part, humans just have to deal with capitis, which can be itchy, but won’t ever spread any diseases to you. I could also get into the other two raptera species that can visit us — one of them you probably know by its common name, crabs, and another evolved more recently to live in clothing seams — but how about we leave that for another time.

Meanwhile the rest of the animal kingdom needs to deal with us and our snotty noses, devouring appetites, and messy reproduction processes that multiply our numbers to dominate every habitat on Earth while quivering at thought of anyone visiting our own.

Ultimately, it’s just more head-habitats for the capitis, so they must be thrilled.

And so our lineages live on, tangled together for millions of years in one of the oldest human–parasite relationships on Earth — going all the way back to the time our ancestors split from the chimps, just thriving away on a speck in the cosmos, like bffs.

Precious isn’t it?

Anyways, sweet dreams you filthy animals.

Doug